It is easy to overlook the ground beneath our feet. We walk on it, build on it, and pave over it. But to dismiss soil as merely “dirt” is to ignore one of the most complex and vital ecosystems on our planet. Soil is the living, breathing skin of the Earth. Without it, life as we know it would simply not exist.

At its core, soil science is the study of this natural resource—how it forms, how it functions, and how it sustains us. It is the only ecosystem that actively integrates the four major earth systems: the lithosphere (rock), biosphere (living things), atmosphere (air), and hydrosphere (water).

Whether you are a master gardener looking to optimize your harvest or simply curious about the natural world, understanding the science of soil provides a fascinating lens through which to view our environment. Let’s break down the complex dynamics that happen right under our boots.

What is Soil Made Of?

If you were to take a scoop of healthy soil and analyze its volume, you might be surprised by what you find. It isn’t just solid rock particles. A healthy soil structure acts like a sponge, balancing solid material with open space.

According to soil science experts at Cornell University, an idealized volume of soil is actually 50% pore space. The solid components—minerals and organic matter—make up the architecture, while the pores allow for the movement of life-sustaining elements.

The Typical Composition of Healthy Soil:

- Minerals (45%): This includes sand, silt, and clay particles derived from weathered rock.

- Air (25%): Soil needs to breathe. Air pockets provide oxygen for plant roots and microbes.

- Water (25%): This fluctuates with weather, but water is the medium that transports nutrients to plants.

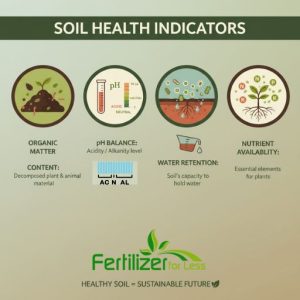

- Organic Matter (5%): This is the “magic” ingredient—decomposing plant and animal residues that fuel the biological activity of the soil.

This balance is critical. If you compact the soil (crushing those pore spaces), air and water cannot move, and the system suffocates.

How Soil Forms: The Five Factors

Soil doesn’t just appear; it is created through a slow, deliberate process called pedogenesis. In the late 19th century, pioneering scientists like Vladimir Dokuchaev and later Hans Jenny developed a framework to explain this. They identified five master factors that interact to create the diverse soils we see today.

Here are the five factors that determine what kind of soil you have:

- Parent Material: This is the starting point—the underlying bedrock or deposits (like volcanic ash or river sediment) that weather down to form the mineral base.

- Climate: Temperature and precipitation dictate how fast rocks weather. Warm, wet climates create soil much faster than cold, dry ones.

- Topography: The shape of the land matters. Steep slopes often have thin soils because water runs off quickly, while valleys accumulate deep, rich deposits.

- Biology: Plants, animals, humans, and microorganisms mix the soil, recycle nutrients, and add organic matter.

- Time: Soil formation is incredibly slow. It can take hundreds of years to form just one inch of topsoil.

Soil Architecture: Texture and Structure

When we talk about “soil types” in a garden context, we are usually referring to texture. Texture is determined by the relative proportions of the three mineral particle sizes: sand, silt, and clay.

Understanding these properties is essential for managing land effectively.

- Sand: The largest particle. It feels gritty and allows water to drain through it very quickly.

- Silt: Medium-sized particles. They feel floury when dry and smooth when wet.

- Clay: The smallest particle. It is sticky when wet and hard when dry. Clay is chemically active and holds onto nutrients well, but it drains poorly.

Topographical maps like this one below courtesy of Blue Jay Painting (Licensed Photo) showcase the dramatic changes we’ve made to our landscape through agricultural practices:

Comparison of Soil Particle Properties

To help you visualize how these components behave differently, we’ve broken down their key characteristics in the table below.

Property | Sand | Silt | Clay |

|---|---|---|---|

Particle Size | Large (visible to the naked eye) | Medium (microscopic) | Small (microscopic) |

Water Retention | Low | Medium | High |

Airflow (Aeration) | Excellent | Good | Poor |

Nutrient Storage | Low | Medium | High |

Compaction Risk | Low | Medium | High |

Feel | Gritty | Smooth/Floury | Sticky |

Most healthy soils are a “loam,” which is a balanced mixture of all three. This combination provides the drainage of sand, the water retention of silt, and the nutrient-holding capacity of clay.

The Chemistry and Biology Beneath

Soil is not a static container for plant roots; it is a dynamic chemical and biological factory.

Chemical Dynamics

The ability of soil to support life often comes down to chemistry. One of the most important concepts is Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC). Think of clay and organic matter particles as having a negative electrical charge. Many plant nutrients (like calcium, magnesium, and potassium) carry a positive charge. The soil particles act like magnets, holding onto these nutrients and preventing them from washing away, yet keeping them available for plant roots to exchange and absorb.

pH is another critical factor. It acts as a “gatekeeper” for nutrients. If the soil is too acidic or too alkaline, certain nutrients become chemically locked up and unavailable to plants, regardless of how much fertilizer you add.

The Living Ecosystem in One Teaspoon of Soil

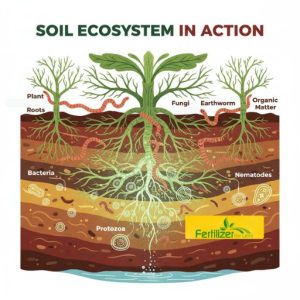

Perhaps the most exciting frontier in modern environmental science is soil biology. A single teaspoon of healthy soil can contain more microorganisms than there are people on Earth.

Key Biological Players Include:

- Bacteria: They perform critical chemical exchanges, such as converting atmospheric nitrogen into a form plants can use.

- Fungi: Mycorrhizal fungi form vast underground networks that attach to plant roots, effectively extending the root system by thousands of times to hunt for water and nutrients.

- Macrofauna: Earthworms, beetles, and termites physically churn the earth, creating channels for air and water (bioturbation) and shredding organic matter for smaller organisms to eat.

Why Soil Science Matters

We treat soil science as a niche academic subject, but its implications are global and personal. The research conducted by institutions like Lancaster University and Cornell University highlights that our management of soil directly impacts food security, climate change, and water quality.

Soil acts as a massive carbon sink. Organic matter is essentially stored carbon. When we degrade soil through excessive tilling or chemical overuse, that carbon is released into the atmosphere as CO2. Conversely, restorative practices that build organic matter can help sequester carbon and fight climate change.

Furthermore, soil acts as a natural water filter. As rainwater percolates through the pore spaces, physical, chemical, and biological processes remove pollutants before that water reaches our aquifers.

Frequently Asked Questions About Soil Science

We know that soil science can get technical quickly. Here are answers to some of the most common questions we receive about the ground we stand on.

1. Is “soil” the same thing as “dirt”?

Technically, no. In the field of environmental science, “soil” refers to the living ecosystem in its natural place, complete with structure, biology, and layers. “Dirt” is what you have when you displace that soil—it’s soil that has lost its structure and context (like the mud on your shoes).

2. Can you change your soil type?

You cannot easily change the mineral texture (the percentage of sand, silt, and clay) because that is determined by the geology of your area. However, you can change the soil structure. By adding organic matter (compost), you can improve the drainage of heavy clay soils and the water retention of sandy soils. Alternations to the pH are also possible.

3. How long does it take for soil to regenerate?

Soil is technically a renewable resource, but it regenerates very slowly. Under natural conditions, it can take 500 to 1,000 years to form an inch of topsoil. However, with active management and organic inputs, we can rebuild soil health and fertility much faster—often within a few years.

4. What is the most important thing I can do for my soil?

Protect the pore space and feed the biology. This means minimizing physical disturbance (like excessive tilling), keeping the soil covered with plants or mulch to prevent erosion, and adding organic matter to feed the microbial life.

Conclusion

Understanding the science of soil shifts our perspective from viewing the ground as an inert platform to recognizing it as a vital partner in our survival. It is a dynamic interface where geology, chemistry, and biology meet.

Whether you are managing a large agricultural plot or a small backyard garden, taking a “soil-first” approach is the best way to ensure long-term success. By respecting the complex architecture and living systems beneath us, we don’t just grow better plants—we contribute to a healthier planet.